Power plant and forst in Poland. Photo djedzura, iStock

Separating land carbon uptake from net-zero emissions

How are net zero emissions defined? It matters. It is the difference between either halting or continuing global warming, writes senior researcher Glen Peters in this blog about a new study published in Nature.

How are net zero emissions defined? It matters. It is the difference between either halting or continuing global warming.

The key is how “removals” are defined, and the role of humans. In a new study, led by the University of Oxford, co-authored by Glen Peters from CICERO and published in Nature 18 November, the scientists are discussing the issue and indicating where potential solutions may lie!

IPCC Assessment Reports

Last week we released the 2024 version of the Global Carbon Budget. One of our iconic figures shows the main sources and sinks of carbon, and the observant will notice that land appears twice!

The two different land fluxes have a rather significant meaning in the context of net zero emissions!

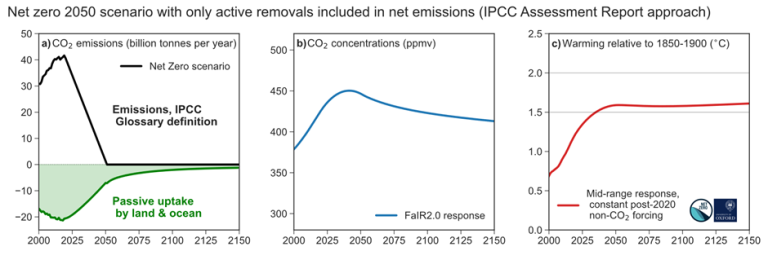

The IPCC Assessment Reports (ARs) define anthropogenic removals as “the withdrawal of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from the atmosphere as a result of deliberate human activities.”

In the Global Carbon Budget (GCB) the anthropogenic sources are from fossil co₂ emissions and land-use change co₂ emissions; land-use change requires the land-use to change (forest to crops, crops to forests, but also temporarily as in wood harvest and regrowth).

The removals in the land and ocean are often called “natural carbon sinks”. In the paper we also call this “passive” removal.

The natural carbon sinks are critical. They soak up around half of our current emissions and when we reach net zero CO2 emissions, they cause CO2 concentrations to decline.

It is the declining CO2 concentrations that lead to stable temperatures! The land and ocean sinks are not included in the definition of net zero emissions, as they are a response of the system.

By chance, the cooling effect of the carbon cycle and the warming effect of the climate system approximately cancel, sometimes called the Zero Emissions Commitment (ZEC) and is close to zero. This means that temperature is approximately proportional to cumulative co₂ emissions. These are two of the most fundamental concepts in climate science.

IPCC Reporting Guidelines

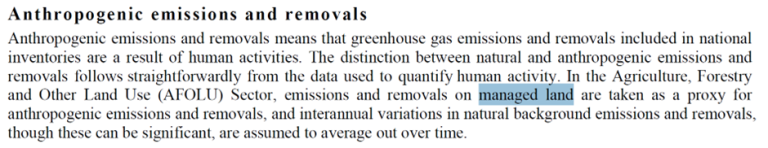

In IPCC Reporting Guidelines (GLs), used by countries when reporting to the UNFCCC, anthropogenic removals are defined those occurring on ‘managed land’.

Managed land is “land where human interventions and practices have been applied to perform production, ecological or social functions”.

That is quite a broad definition, and perhaps not surprisingly, nearly all developed countries define all their forests (and land) as managed. Exceptions include Canada (unmanaged land), Greece, and Russia.

On managed land, which in many cases is all land, both anthropogenic and natural carbon removals (active and passive) are captured. This is believed to give the best estimate of total carbon removal, but it cannot differentiate between natural and deliberate human activity.

Thus, the IPCC reporting definitions capture a significant portion of the removals that IPCC assessment reports would allocate to non-anthropogenic activities.

The differences between definitions are more than just academic. More than one-half of the passive sink is estimated to be managed based on country reporting, the remainder is called ‘unmanaged’.

When the managed land sink and the active land-use change are combined, the LUC emissions from the Global Carbon budget go from around 4Gtco₂ per year to a net removal of over 3Gtco₂ per year, a difference of around 7Gtco₂ per year.

That net CO2 uptake on land is still the same, but the split between anthropogenic and natural is different in the Global Carbon Budget and national GHG inventories.

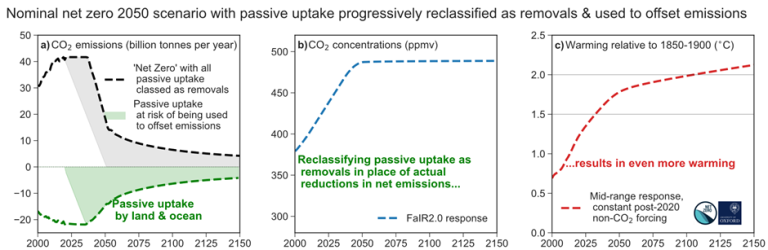

Does this matter. Well, yes, it does. In the most extreme level, it is the difference between stabilising temperature and increasing temperature.

If the sources and sinks of carbon are simply balanced, then the atmospheric co₂ remains constant. This leads to increasing temperature, until a new equilibrium is reached (the Equilibrium, Climate Sensitivity, ECS). This is not the outcome we want.

This is an extreme example. If only some of the natural sink is allocated to anthropogenic removals, the difference will be smaller.

The model used in these calculations (FaIR2.0) is rather well behaved, using another model, the passive uptake actually becomes a source at the end of the century.

Getting the definition right

We need to get the definition of net zero co₂ emissions correct.

Net zero co₂ emissions have been defined based on the Global Caborn Budget definition of land use emissions, active emissions and removals caused by direct human activities.

If net zero co₂ emissions are instead defined based on emission reporting definitions, including a large share of passive uptake, then ‘net zero co₂ emissions’ will not stabalise temperature but lead to further warming.

The problem arises since, for good reasons, the IPCC assessment reports and IPCC reporting guidelines developed largely independently, which was fine, until net zero emissions became relevant!

The irony is that both sets of definitions come out of the IPCC! There was an IPCC Expert Meeting in July 2024 to discuss this issue and look at ways to move forward!

Country-level results

The discussion above has focused on the global level. What about the country level?

Because countries have different relative shares of forests and co₂ removal on land, the differences at the country level can be more significant.

Sweden, for example, already has net zero GHG emissions using the NGHGI emissions, despite the fact it continues to have significant active emissions. Whilst Sweden does not argue it should be allowed to offset all its emissions with LULUCF, this may change politically over time and other countries may view this differently.

If Sweden claimed that it was net zero GHG emissions, and all countries followed with the same definition, then global temperature would continue to rise after net zero emissions. To avoid rising temperature using the definitions as in the IPCC Reporting Guidelines, would require countries to go net negative.

Who is claiming natural sinks as anthropogenic removals?

The EU and US both include all their LULUCF sink as anthropogenic in their climate targets, which means they claim all their natural carbon sink as anthropogenic. This is inconsistent with the science of net zero. Some of the LULUCF sink will be truly anthropogenic, others will be natural.

The EU, however, has an additional constraint on the size of the sink, to be at least 310Mtco₂/yr. Preferably, the EU and the US should have a net zero target excluding the LULUCF sink, but additionally have a target to maintain the LULUCF sink, as long as it is not used to offset continued fossil emissions.

The way land use emissions are included in EU legislation requires Sweden to maintain its sink, and contributes to the EU LULUCF target of 310Mtco₂/yr. This would mean, all-else-equal, that Swedish removals (LULUCF) would be maintained. The degree to which Swedish emissions went to zero would then depend on its share of the EU’s residual ~310Mtco₂/yr emissions in 2050.

Policy implications

There are two key implications for net zero policy:

-

We need Geological Net Zero (GNZ): meaning one tonne of co₂ permanently restored to the solid Earth for every tonne still generated from fossil sources

-

The natural sinks need to be protected, as they are needed to bring atmospheric co₂ concentrations down to ensure warming is halted.

These two targets need to be kept separate, otherwise fossil emissions can be offset by natural sinks.

This is a complex issue, and it will be challenging for countries to deal with, but it is solvable. The Kyoto Protocol solved it with complex accounting rules. The Paris Agreement allows countries to decide themselves what to do. That means it is up for science to point out when net zero pledges are not in line with halting global warming.

Read the article: Geological Net Zero and the need for disaggregated accounting for carbon sinks, Nature.