CAN KNOWLEDGE FROM PEACE-BUILDING PROCESSES HELP SOLVE THE EQUITY CASE FOR CLIMATE CHANGE? PHOTO: COURTNEY BOYDSTON @ FLICKR

Sharing global climate responsibility – how to resolve the conflict?

Who is responsible for climate change? How to break the equity deadlock? These questions have been hanging over international climate talks since several decades.

Developing countries – the victims, expect that the culprits – the rich, industrialized countries in the West, take responsibility for solving the climate problem. Yet the latter refuse to take on the full responsibility. How to break the equity deadlock?

Putting figures on responsibility not easy

Natural scientists at CICERO are increasingly able to put numbers on the climate responsibility of different countries. Yet many questions are open still, explains Ragnhild Bieltvedt Skeie:

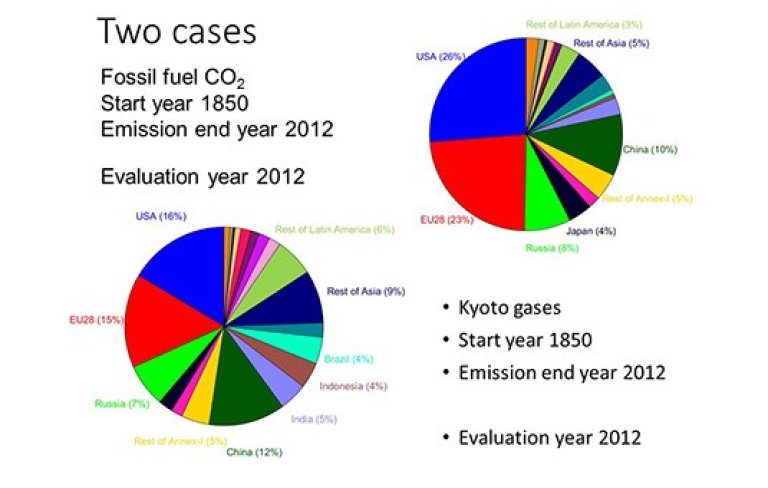

“The results vary greatly according to the method you apply. Firstly, what is the starting year of the calculations? Shall we take 1850, the start of industrialization but before we knew about climate change effect of fossil fuels, or 1990, the base year of the Kyoto protocol? Secondly, which gases to include? If you limit calculations to only fossil fuels, the US and the EU stand for about half of the historical emissions. But if you also include other greenhouse gases, for instance those emitted by rice fields in Asia or deforestation in the Amazonas, the share of the US and the EU shrinks to about one third and Asia’s or Brazil’s share increases,” she says.

Including the full emissions supply chain, i.e. not only emissions from consumption but also from extraction and consumption, gives oil and gas producing nations a much bigger responsibility.

“If you look at emissions per capita for the full emissions chain, then a small country like Norway has the biggest historical emissions, while it also is among the world’s biggest emitters today,” says Skeie.

With so many open questions, calculations of historical responsibility are difficult to use in climate negotiations. But they have not stopped the blame game between developing and developed countries.

Transitional justice – a new approach

Sonja Klinsky, Assistant Professor at the School of Sustainability, Arizona State University, has been looking at the fear and high emotions that lie behind this deep tension.

“Developing countries perceive climate change as an injustice: they have not caused the problem, while they endure the most climate impacts and are now being told by others to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Developed countries, on the other hand, are afraid of liability and being held fully responsible for climate change forever,” says Klinsky.

She continues: “We have been going in circles for decades. Out of frustration, I looked beyond the climate space for inspiration. There are interesting lessons to be learned from transitional justice processes.”

Transitional justice processes are peace-building processes in countries that have experienced civil war or human rights abuses against its populations. Typically, these conflicts are historically rooted, while victims and perpetrators are bound to build a new future together. Similarly, the world is confronted with climate change, which is partly a historical problem, inflicted by some, but with consequences for all, and we are bound to cooperate globally about solutions.

“Let’s take South-Africa as an example,” explains Sonja Klinsky. “After the fall of the Apartheid regime, black and white had to transform the South-African society completely. The judicial authority limited: many had supported the regime, it was difficult to pin individual responsibility. Instead they took a path of transitional justice: they changed their societal structures and institutions, shifting the future power balance.”

Climate diplomacy could also profit from the methods used in transitional justice processes, according to Klinsky: “Transitional justice offers new, creative ways of discussing responsibility without entering into difficult liability discussions. It is about identifying long-term institutional changes that would divide opportunities more equally from the perspective of developing nations. For instance, giving them access to technological development, social support or education.“

New situation after the Paris Agreement

This was applied, to some extent, in the Paris Agreement. The agreement, which was concluded last December, managed to sideline the equity deadlock by changing the way in which countries’ contributions are defined:

“Firstly, the agreement builds on national pledges that were submitted upfront, without internationally agreed equity principles. How fair the outcome becomes is largely depending on the decisions made by each country nationally, and not on international negotiations. Secondly, the Paris agreement differentiates the efforts of countries in various ways and no longer based on the convention's equity principle,” explains Steffen Kallbekken, director of Center for International Climate and Energy Policy (CICEP).

This does not mean the equity debate is over, but it will largely be driven by civil society and shifted to the national level. Internationally, the discussion has moved from how much each country should cut, to who is responsible for loss and damage caused by climate change.

"The Paris agreement rules out compensation linked to climate damages, but the responsibility for causing the damages is still likely to be a major topic for the next few years,” says Kallbekken.

“For instance, there will be a new insurance scheme. Who should pay for this scheme, and other elements such as early warning systems? Should this in any way be linking to responsibility, or capacity?"

The discussions between developing and developed countries on responsibility for the climate problem are long but settled.

CICEP-director Steffen Kallbekken sums up the development within UNFCCC 100 days post Paris. The interview is in Norwegian. Video by CICERO.