Photo: Trail / Unsplash

Balancing fairness and ambition

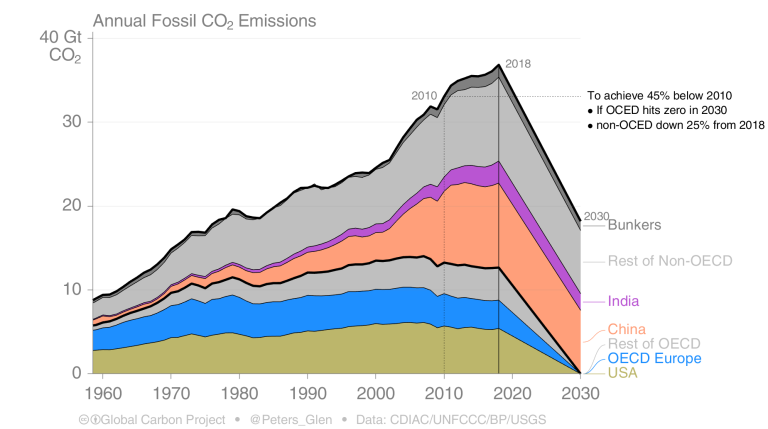

A headline result from the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C was that global co₂ emissions need to decline by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030. Is this possible while still retaining fairness in mitigation?

It is easy to throw around numbers, and “cut emissions in half in the next decade” is consistent with 1.5°C and easy to communicate. It was a headline from the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15) and will no doubt be a focus at this year’s UN Climate Summit. But what does it mean for individual countries?

Each country could be asked to cut CO2 emissions in half in a decade (more specifically, reduce CO2 emissions 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, as stated in SR15). No exceptions. The fairness police would, rightly, come out. Rich countries should do more: they are already developed to meet their needs (even if unfairly distributed), they caused the problem (even though they didn’t know at the time), they have greater capacity to adapt, and hey, they can afford to mitigate.

Another extreme would be to require all OECD countries to get to net-zero emissions by 2030. To still reduce global CO2 emissions by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 would require all non-OECD countries to reduce emissions by 25% from today’s levels. Sounds reasonable, maybe? But is that fair for non-OECD countries?

Let’s have a look at a few countries, ordered by the top CO2 emitters (on an aggregate, not a per-capita basis). Those top-4 countries are China (28% of global emissions), US (15%), EU28 (9%), and India (7%). Together, they cover 59% of global emissions.

The top-4 are also an extremely diverse group of countries. That is not to say that the other 41% are not important. They are equally important, but that importance is spread over some 150 or more countries.

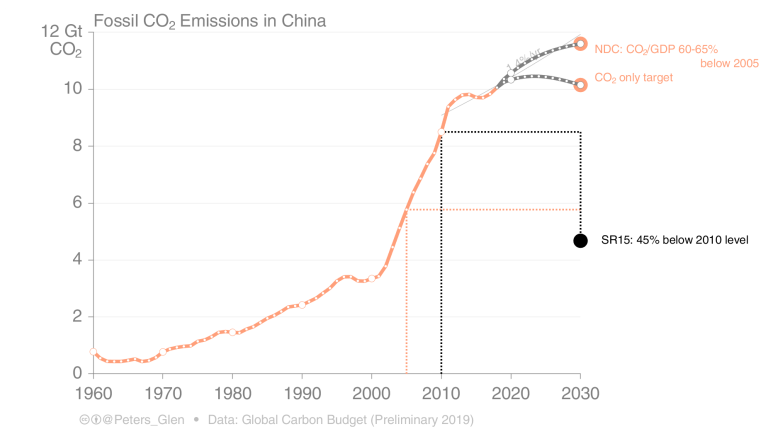

China has pledged to reduce its CO2 emission intensity (CO2/GDP) by 60-65% below 2005 levels, and peak emissions before 2030. Some argue China has already peaked CO2 emissions. Perhaps it has already done this? To estimate future emissions requires GDP projections. I have used GDP in Purchasing Power Parity, and used GDP projections from the OECD.

Chinese CO2 emissions grew rapidly in the 2000s, but have slowed down and even declined since 2010. Emissions are rising again. Based on its emission pledge, and GDP projections, China may peak its emissions in a few years or as late as 2030. Emissions could, best case, be the same as they are today, or if current emission trends continue, grow by about 20% by 2030.

China’s pledge is far from 45% below 2010 levels by 2030. Even a 25% reduction by 2030, assuming OECD countries went to net-zero by 2030, is far beyond what China has pledged. Despite a slowdown in recent years, current emission trends put China more on a path for a peak towards 2030.

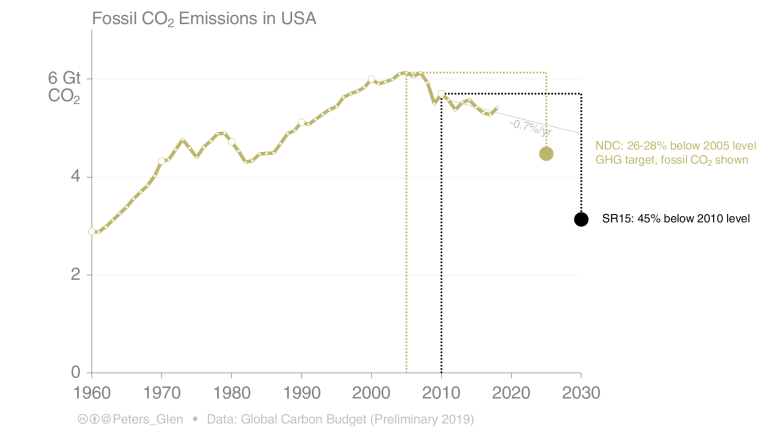

The USA has surprised many, with CO2 emissions declining at a reasonable pace since 2007. U.S. emissions have declined because of slightly lower energy use, probably with some help from the Global Financial Crisis, and particularly a strong shift away from coal and towards gas, solar, and wind.

While emissions are edging down less than 1% per year, the U.S. is not on track to meet its emission pledge in CO2 terms (the GHG target is 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025).

For the U.S., to get close to 45% below 2010 levels by 2030 will be a challenge, although quite possible. It would require a substantial acceleration in emission reductions to 2025, and then again to 2030. For the U.S. to get to net-zero by 2030, that is another question, and would seem highly unlikely given political, social, and technological inertia.

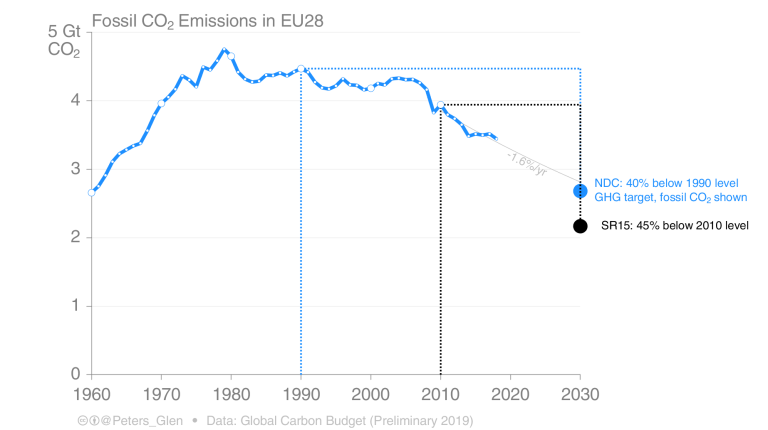

The European Union (EU28) has been steadily reducing CO2 emissions, speeding up after the global financial crisis, but emission cuts have recently slowed down. Like the U.S., the EU emission declines since 2007 have benefited from slower economic growth after the global financial crisis.

In terms of CO2 emissions, the EU28 is on track to meet its 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 (the target is in GHGs). Only slightly more ambition is needed to reach 45% below 2010 levels by 2030.

The EU28 certainly has the scope to reduce emissions faster and give ‘more space’ for less well advantaged countries. The EU is looking at a net-zero target around 2050, but bringing that forward to 2030 would seem a rather big stretch given already existing political challenges with raising current 2030 or 2050 ambition.

India is called the climate leader by many, and, under some definitions, it is the only major economy to have an emission pledge compatible with 2°C. India can only be a climate leader under extreme interpretations of equity, which also depend heavily on future emission pathways with large-scale negative emissions.

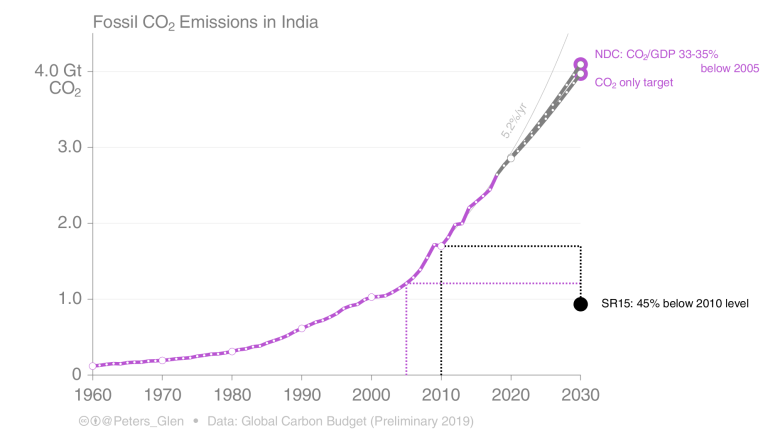

Despite impressive growth in renewables, India’s CO2 emissions continue to grow strongly. India’s emission pledge, to reduce CO2 emission intensity by 33-35% from 2005 levels by 2030, when linked with growth in GDP, leads to a rapid increase in emissions, only slightly below today’s growth rates of over 5% per year.

India is nowhere near cutting emissions by 45% below 2010 levels by 2030, and on current rates, the country's emissions will exceed that target by about 3GtCO2, a level greater than India’s current emissions. That emission gap would have to be picked up by another country, or group of countries.

Which countries would be willing to pick up the slack for India growing its emissions substantially?

Masking the challenges

Catch phrases such as 'halving emissions every decade', potentially mask the mitigation challenges, particularly for developing countries.

Even if rich countries did the most extreme that they are asked, hitting zero by 2030, this still leaves a huge burden on developing countries. India is looking to grow emissions by 50%, not cut emissions, nor 25%, nor 50%.

I don’t mean to pick on India. India needs more growth, more development, and a lot more leeway. But the maths is clear. If the world wants to stay below 1.5°C, developing countries must achieve their development objectives whilst cutting emissions radically. Not in the distant future, but now. This must happen while rich countries get to net-zero in a decade.

Going negative

It has become well-known that most mitigation scenarios have extreme amounts of carbon dioxide removal (negative emissions). Collectively, the pathways that are used to derive the target of 45% below 2010 levels by 2030 include large-scale negative emissions. The negative emissions include both natural methods (afforestation, reforestation), as well as engineered methods (like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage).

Many are critical to negative emissions, even myself, but scenario analysis suggests they are needed. If you reduce the amount of negative emissions, then short-term emission reductions are even more extreme.

If global emissions need to reach zero by 2050, and negative emissions are excluded, then all countries, every single one, must be zero by 2050. Fairness can’t get around this physical constraint.

While negative emissions are often critiqued on equity grounds, negative emissions are what allows equity to be achieved!

Acknowledging the challenge

The maths of cumulative emissions is cruel. Cumulative emissions are not fair. And the mitigation burden on developing countries is one reason why I say 2°C is not possible. Don’t ask what I think of our chances of staying below 1.5°C.

That does not mean we don’t try for 1.5°C. It does not mean I am defeatist. In the words of Rob Socolow, “What's fair is no longer safe. And what's safe is no longer fair” (apparently).